We are accustomed to thinking of technology as something that provides us with greater abilities.

Our phones and computers allow us to communicate with almost anyone anywhere, so long as they also have a device with which to connect to a shared platform. Our vehicles allow us to travel farther and faster. Our microwaves provide near instant heating of food, and so on. One can point to just about any aspect of our modern world and ascertain some extra ability it provides.

It is important to think, however, about how this world that we’ve created for ourselves also acts to limit us in certain ways, inhibiting and closing off opportunities for different experiences.

Reality, in other words, is prescribed and delimited by technology, by the tools we use and the methods those tools allow for interacting with the world around us.

I’ve written before about how this world that we build for ourselves can also trap us, using the suburb and its car dependency and, conversely, the 15-minute community to illustrate limitations and possibilities, respectively.

A week or so ago something happened that caused me to think about this in a slightly different way, about how these limitations manifest to be self-reinforcing, such that traps lead to more traps, unknowns to more unknowns, creating an increasingly limited set of options.

Not only, in this circumstance, are there options that are known yet cannot be accessed, but options that might be available and viable recede from the horizon of our awareness. These are the “unknown unknowns”, to quote Donald Rumsfield, and, while we don’t know what those are, we can enhance our prospects of knowing them by acknowledging that they might be there.

I will get to what happened to cause me to think more about this dynamic in a bit, but first I want to offer what might be the biggest example of this dynamic.

It’s always struck me as profoundly absurd that we continue to barrel towards an increasingly risk prone future simply because it is too difficult to change the way our economy has been operating for the past 100 years.

Yet, this is exactly what is happening with climate change.

Just this week scientists warned that global warming may breach the 1.5° mark by 2027. As the 2° threshold nears, so too do tipping points – it becomes difficult for phytoplankton, which store massive amounts of carbon, to survive at this point, for example, and their loss is likely to trigger a cascade of events that further increase temperatures.

There’s reason to believe that tipping points aren’t necessarily the final straw, natural systems do have powerful regulatory mechanisms that can, if helped, act to restore some degree of balance in the biosphere, but it’s an increasingly difficult task as we continue down that road. (For reasons why tipping points do not necessarily lead to runaway warming see this article.)

And yet, no matter the severity of warnings, the increasing certainty of the harms that we are exposing ourselves and our children to, we remain trapped in a system that continues to bring us ever closer to the precipice.

This is the self-fulfilling rationale of technology. A system of interconnected elements that falls apart if one fails, such that it both justifies the whole and justifies each and every subcomponent. We cannot move away from personal vehicles because we’ve been building our communities around them for the past 70 years. Without a car many of us wouldn’t be able to access food or visit the doctor or purchase clothes.

And because we rely on cars to get around during everyday life we come to accept their presence as inevitable. The work of imagining what our suburban communities would look like, not to mention how they would actually function, without cars is a challenge that easily confounds even the most creative mind.

Cars and suburbs and sprawl are examples that, perhaps, I use too frequently, but they are extremely good ones in this instance. The suburbs, associated consumerism and “keeping up with the Joneses”, act to reinforce conformity, much as we might prefer to ignore that fact, and in doing so, I believe, help generate the imaginative malaise in which we lose the possibility of discovering unknown unknowns.

This mental, social, cultural malaise acretes through the technologies we surround ourselves with – we habituate to our home, finding our way up the steps in the dark, knowing where the light switches are, the easy dance of finding utensils in the kitchen while preparing a meal. The suburban community is just one powerful example of this.

The event, that I noted above caused me to think more deeply on this issue, has more to do with how this habituation affects our sense of self, constraining and defining that self and, in doing so, also closing off possibilities for that self to become something other.

This event was someone taking their own life. I didn’t know this person well, but the context in which this happened, the failure of a business to which this individual was central, brought home to me just how powerfully societal expectations can influence our sense of self, shaping it to the degree that absent attainment of those expectations, or perhaps some degree thereof, we have very little left of a self that we might otherwise be.

This absence of possibility outside of what the roles and expectations that our social and cultural dynamic provides is a very real thing, and it seems to be growing. The targeting of trans and gender non-conforming identities by politicians and culture warriors is one disturbing example. Another, more mundane, example is the decades-long diminishment of arts and humanities in higher education, with its corollary shift toward outcome oriented education.

In all of these cases there is a narrowing of what is acceptable, of what is valued. The outcome is, by and large, predetermined, and the role of the individual is to simply slot into what that outcome demands. To the extent that the individual is not able to meet the demands of that role, their value, as such, is greatly diminished.

I don’t mean to discount the value of fitting into and finding a sense of meaning with a larger endeavour, in fact I think that is among the most important and worthwhile things we can do as members of a society. I do think it’s worth considering the demands that society places upon us, how these demands are formed, and the ways in which they take a toll on who we are as individuals and our ability to live meaningful lives.

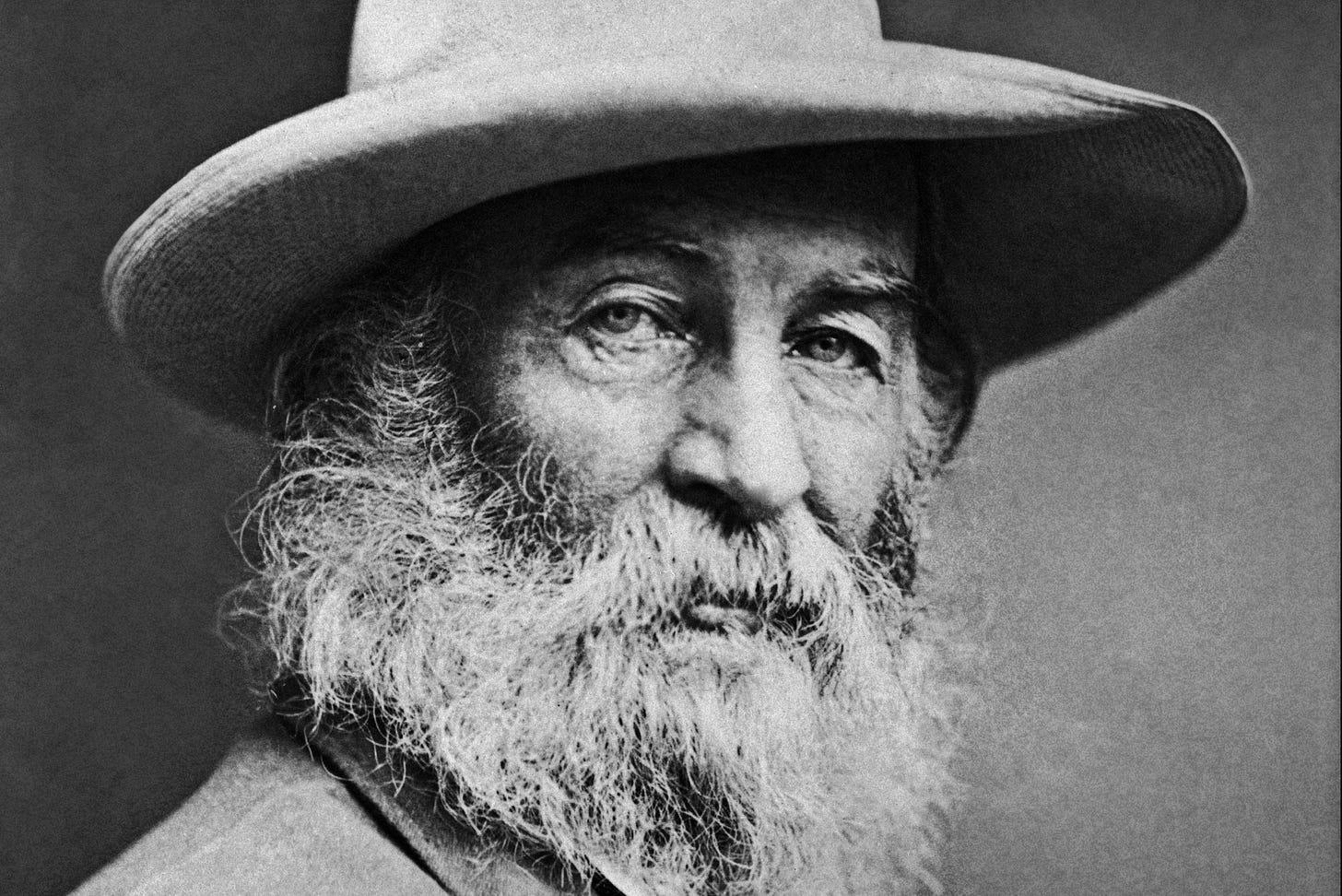

Opportunities to step outside of the machine, the technology or technique that we’ve developed as a society for operating to achieve outcomes, need to be far more prevalent and valued than they currently are. Opportunities for idleness, for not producing, for disengaging and disconnecting, for experiencing oneself. As Walt Whitman put it, “I loafe and invite my soul…”

Leaves of Grass

Song of Myself 1

I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. I loafe and invite my soul, I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass. My tongue, every atom of my blood, form'd from this soil, this air, Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same, I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin, Hoping to cease not till death. Creeds and schools in abeyance, Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten, I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard, Nature without check with original energy.

Weekly News Digest

Eco-facism is on the rise, and for those of us in the environmental community it is important that we are able to identify it and take steps to counter it. This is a good article outlining how it’s increasingly being adopted by those on the far right to agitate against compassion for those impacted by the climate change.

The first step to preparing for surging climate migration? Defining it.

And a little more on the topic of opening ourselves to the wonder of the world from The Maginalian.