Doritos, the 8th wonder of the world.

The puff of cheese vapor released upon opening the bag, the comfortingly uniform triangle shape, the intensifying aroma as the chip comes nearer, the crunch, the mouth watering, the enveloping umami, slightly old, slightly funky, slightly sweet, definitely salty, and then, when it’s all done, the residue left on the fingers. The Dorito chip is possibly the most commercially successful snack food ever produced.

Eating one is a near perfect sensory experience, brought about by a combination of dumb luck, intense research and precise engineering. This combination of effort and luck produced something that has been wildly successful for its ownership, and, if I’m being honest, pretty darn successful for my tastebuds.

Now, you may be wondering why I’m talking about Doritos on an environmental blog. Doritos aren’t necessarily terrible in any environmental sense, but the knock impacts that they, and junk food generally, have upon society – the costs they place upon the rest of us – helps illustrate some of the dynamics that are at the root of environmental and social problems, including climate change.

This dynamic is known in economics as negative externalities.

Negative externalities are costs or impacts that an action, such as the production of a good, have upon society that aren’t included in its price. Put another way, these are the costs associated with a product or activity that aren’t experienced by those most directly responsible for it.

With respect to Doritos the price we pay at the checkout counter does not include the costs that they, and the larger junk food category to which they belong, have upon society. These include an increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, to name a few.

All told, the negative externalities of unhealthy eating in Canada are estimated at roughly $14 billion per year. These costs are borne by our healthcare system, paid for, in turn, by our taxes. They are not paid for, however, by those most directly responsible for the problem, namely the fast food companies such as, in the case of Doritos, Frito-Lay. The costs of the negative impacts of their product, in other words, have been shifted onto the public, allowing the company to generate more revenue.

It isn’t all that hard to see how negative externalities are a big deal for the environment.

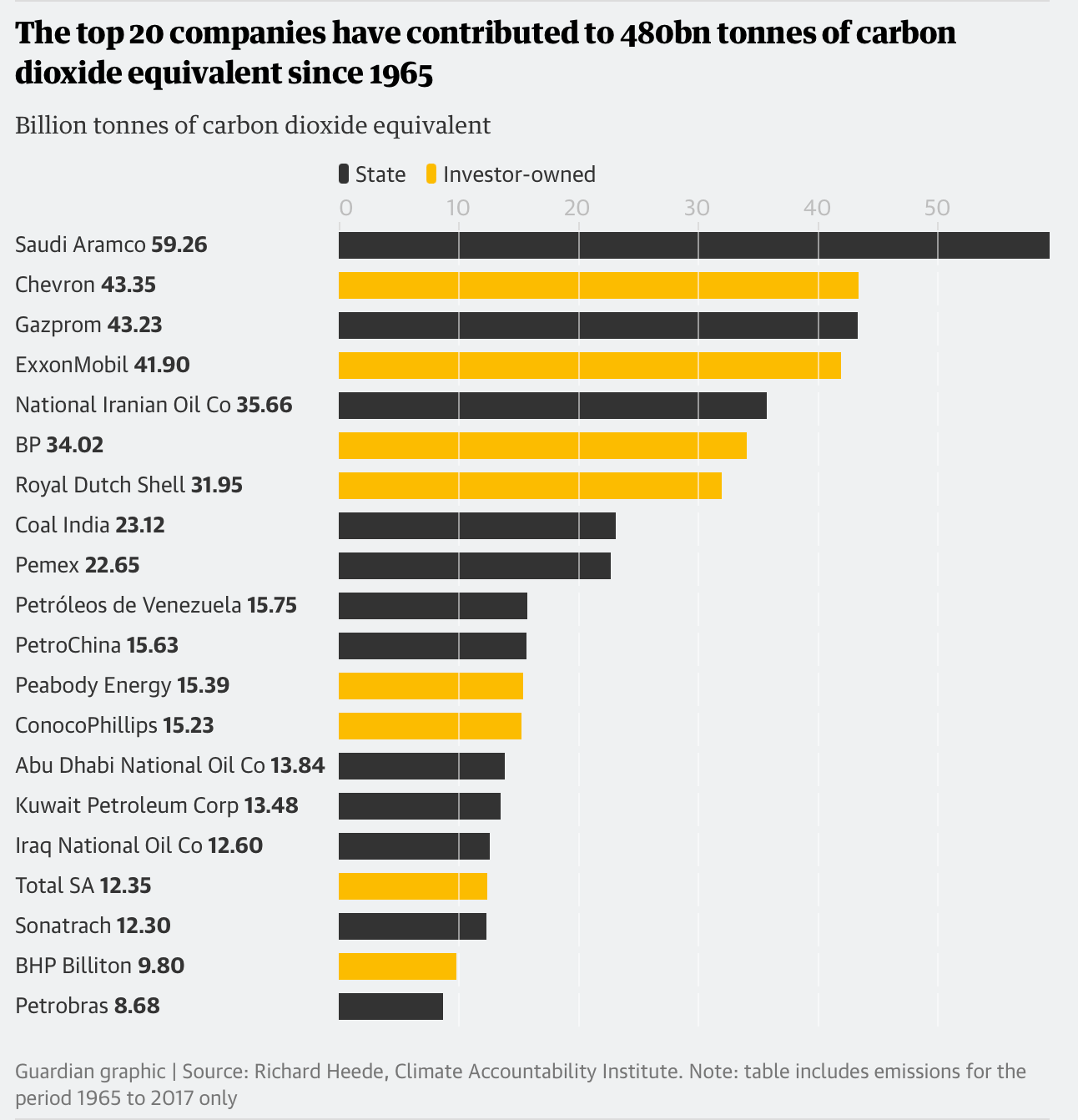

Oil and gas companies have profited for a hundred years due to their ability to avoid costs associated with their activities. They use the air that we breathe, our atmosphere, as a dumping ground for the negative externalities of their product. After a hundred years the atmosphere, what they have used as a free dump site, has filled up.

There are, of course, a couple of key considerations worth mulling here.

Some costs can be seen as worth sharing, such as for a product or activity that provides a significant service to society. We make trade-offs like this all the time. For example, some level of environmental degradation, such as a limited level of noise or air pollution, is generally accepted in return for the convenience that a road or highway provides.

Another consideration is the notion that negative externalities are a result of market demand, that the demand for a product, in other words, justify its social costs or the negative externalities associated with it. Society, in this view, by purchasing the product is making the choice to assume the costs associated with it, voting, as it were, at the counter.

These are fair points, and it’s true that there are benefits, have been and will continue to be, to oil and gas extraction and production.

However, we are seeing what happens when an activity that can be beneficial is not priced properly, when the price it has on the marketplace does not accurately reflect the impacts it has upon society. Priced properly oil and gas internalizes the costs associated with its use, allowing those impacts to be mitigated. This is what a carbon price is meant to accomplish.

Unfortunately, we all too often see efforts to accurately price economic activity subverted. A recently exposed relationship between an environmental law professor at Harvard, Jody Freeman, and the oil giant ConocoPhillips, serves as a case in point.

Freeman is paid $350,000 a year to sit on the board of ConocoPhillips as an “independent director”. Email correspondence, however, shows Freeman facilitating a meeting between the Security and Exchange Commission and ConocoPhillips, at a time when the SEC is considering whether to require companies to publish their carbon emissions.

ConocoPhillips, one of the world’s worst polluters (and proponent of the Willow drilling project in Alaska, the potential emissions of which are widely understood to be entirely incapable for our atmosphere to absorb safely) is using the money it makes, in large part by leveraging negative externalities, or placing the cost of its activities onto the rest of us and let’s now forget, future generations, to advantageously shape the laws that govern it.

(You may be thinking of all the efforts to derail carbon pricing here, and you’d be absolutely right to do so.)

In economic parlance this is known as a market failure, and yet it’s practically routine.

If we look closer to home we see this same dynamic playing out with the development industry, the opening up of the Greenbelt, and the profound changes the Ford government has made to the regulations that govern land-use planning.

The negative externalities, here, include the loss of farmland, the loss of wildlife habitat, of ecosystem services that filter air and water. Additional, and compounding impacts result from the built form these changes to land-use planning seem likely to result in. More sprawl development means more reliance on cars as a primary mode of transportation, more use of aggregate for roads, less walking and cycling and less community cohesion.

The special access to the levers of government that produced these policies derives from a history of taking advantage of our collective space, of placing costs into it so that profit for a few can be maximized.

Ontario has a long history of poor urban planning, and it is largely due to the fact that we have externalized the costs of it onto the public. People spend hours in their car commuting to and from work. This is the cost of cheaply built, poorly planned housing.

If there’s a lesson to be learned here it’s that a lack of understanding the cost of something almost always leads to suboptimal outcomes. Something may taste delicious, may feel really satisfying, and ultimately it might not seem like eating just one bag is a big deal, but put that together with millions of other bags, a billion dollar marketing campaign, and you’ve got an out of control train barreling through the emergency room.